Dr. Nenos Georgopoulos, Chairman of the Philosophy Department at Kent State University, 1978.

Having spent some time marveling at the glass pieces now on exhibit in the main gallery, I wandered further into the KSU Art Building. On the right I passed a drawing class in session. A few steps down the hall I was forced to a halt.

On my left, in a small, unpretentious almost hidden room labeled Gallery, Were I painstakingly arranged a number of what at first seemed crude structures. I spent a few minuets looking through the glass wall. They contrasted sharply with the glass pieces I had just seen. I walked into the room from the side door.

It was an exhibit by Samer A. Tabbaa, a KSU sculptor. I looked about surprised and delighted. It was the first time I had seen an exhibit at KSU, sculpture that was not of the pop, op, or constructivist variety.

Here was stone, pure and simple: sandstone, limestone, alabaster, granite. All the pieces, despite their formal differences, seemed to point not to what one can do with stone, not to the stone as a mere medium for plastic forms, but to the stoneness of the stone, to the material as a forceful contributor to the work of art that each piece developed.

Here was an artist who not only had sacrificed or undermined, but had positively dismissed figurative expression and formal articulation and visible values for the sake of the elemental power and primordial association of stone. He seemed to thrive not on his ideas but on the stone’s resistance to them. His marks and carvings recorded his struggle with a material more telling and more potent than he.

They too told the story of where he had begun expressing his thoughts and emotions – thoughts and emotions which the stone appropriated and which only the stone itself could finish. The entire, rather small exhibit seemed to be a celebration of stone in a somewhat analogous way the work of Hoffman and DeKooning is a celebration of color and pigment.

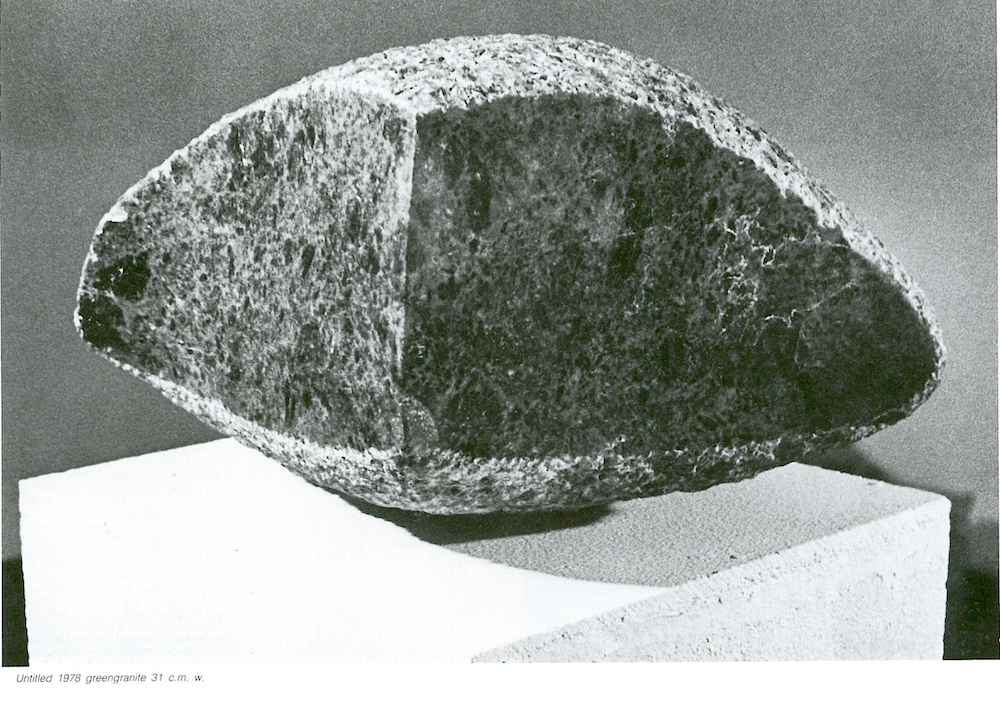

The works are all untitled. In front of me there is a piece of grey – black granite with the illusion of green hovering over it. It is a semi – flattened ball with one part of it cut off and chiseled into two smooth, slightly concave sections. They call attention to and reveal the compact, marvelous interior. The solidity and compactness of the piece asserts itself on the space it displaces. Yet it seems to want to move, to take on other spaces. For although the sculpture has no external referent and carries no allusion to flying, and the deliberate lack of title denies any associative values, nevertheless, that the piece does not set heavily on its base and that the two frontal sections are carved into wing – like forms, evoke in me the image of an arrow or a bird: an eagle in stone.

The combination of the contrary forces – the solidity and heaviness of the stone and the lightness of the image bewilder me. I am forced to return to the elementary plastic value and its tactile compactness.

I reach out and touch it. My hand first runs over, exploiting the smooth, slightly concave, spatially active surface of the two frontal sections. I feel the cool stone, fondle its sheen, trace the lines of directions, becoming more and more aware of the volume. I then curve my hand over the roughness of its skin, sensing the hardness. They wish to determine its mass and ponderability – its solid existence, its compact interior.

I step back. I no longer see with my eyes. It is my hands that assess the volume. I feel the solid mass with my body, in my stomach – the heaviness.

The artist tells me he was lucky to have found this boulder among the scrap in a nearby quarry and that due to the initial shape and the hardness of granite he did minimal work. He is too humble. That was no luck. It takes an artist to find such a stone. We both know that his work as an artist was already underway with his choice of the stone. The piece was chosen because it enfolded aesthetic content which he patiently, respectfully further articulated through his own contributions by means of chisel and hammer. In that sense the artist participated in a developing art work – a process in which the stone, its original shape and its inherent recalcitrance also contributed.

The artist tells me that he has also found the sand stones which are at the rear of the room. They were originally lying by the banks and at the bed of the Cuyahoga River when the city damned it last summer.

I walked over to them. They have no base; they are placed on the floor. They are large grey – brown, almost rectangularly shaped stones with a yellowish carved interior. Like the granite piece, they preserve their natural form. The artists work on them seems to be erosion accelerated – a prediction of what could have happened had the stones been left by the river. Here there is no struggle against the elements. Rather an attempt to show these elements more clearly, to lend a hand to the work of the river: artist and nature merge in the process of creation.

We agreed that the most appropriate place to exhibit them is the river bank where they were found so that they can become part of some future rivers cape. The hope is that another artist might turn his attention to them and continue to open paths to an art work by exploring and revealing the possible ways stone succumbs to and resists the river.

To the right of the river stones and erected on sand is another set of stones, but of different color, size, and texture: an ensemble of 18 limestone’s. They stand vertically with some horizontal pieces on top. Here there is not even the minimal technical control that characterized the granite piece. The way they are carved and they way they are arranged attest to free, intuitive markings. These markings, made as they are with the bush hammer and point, draw attention to the mass of the sculptures.

Although the pieces stand on their own as individual sculptural bodies, they seem to belong together. In formation they evoke architectural associations. Their faded, almost used color, they roughly carved concave surfaces, their rugged contours suggest the ruins of some prehistoric city. But this suggested archaic image is interestingly combined with a modern sculptural device: the pieces can be re-ordered or re-arranged so that one can produce a completely different effect from the spatiodynamic arrangement that the artist himself has set for us.

This effect is multiplied and enriched if we walk around the formation. Viewing it from different angles the shades shift, elongate, and crush on the tall rough columns. The stone project different facades: together they make a different ensemble. One may hurry up or slow down through the half – trapped spaces of the marvelous phantasmagoric sculpture.

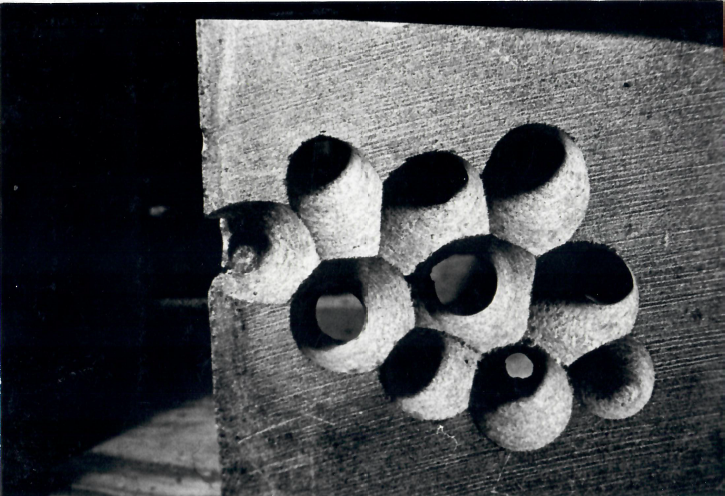

Finally, there is one piece which from the commanding place it has at the show seems to be close to the artist’s heart. It, too, is untitled, but from the way it is displayed and from its shape, it cannot be anything but a tombstone. It is made of two unequaled parts, the larger resting precariously on the smaller. The piece is sand – stone and appropriately so. Sandstone is much more earthy than other stones, looks weathered, almost ancient, and dissolves away easily. On the lower half of both sides of the entire stone there is curved a pattern of successive domes reminiscent of Islamic design. On the upper half of both sides of the entire piece the artist has carved the last poem by Abu Firas, an Arab tenth century romantic poet. The piece, I learn, is a tribute to the poet. Both the design and the calligraphic lettering fit and blend so well with the copper – tinged stone that one might think the whole sculpture was recently unearthed.

Despite the calligraphy and the design, this sculpture, like all the others, does not appeal to the eve. The carved design and letters go deep into the sandy body of the stone – their role is sculptural, not visual. They invite us to go through the grooves with our body and feel the stone’s lack of solidity. Ultimately, this piece, too, is an appeal to tactile sensations.

Whatever personal meanings and associations this piece may have for me, the artist tells me, in the final analysis I must dismiss them for the sake of the stone alone, he says, that is of ultimate interest. ‘Stone carries with it the infinite wisdom of millions of years. It is all there for one to explore.’

And after a pause, ‘I am attracted to its resistance and individuality. I am never sure of what to carve – only of the desire to carve. As my work progresses, the stones break the silence and I listen carefully. Ideas flow as the stone tells me more, and I record the interactions – and, I must add, the struggle too.’